Civil Rights and Colby Junior College

Lack of Racial Diversity and Initial Solutions

In November 19, 1968, the Colby Courier featured an article called “Lack of Blacks?” written by Anne Ambrose. With this article, the writer explains that “The Colby community is very much aware of the lack of negro and foreign students on campus. All of us are losing out because of the insufficient number of students representing these social and cultural groups.” Ambrose goes on to add, “The greatest part of our total education will be through our contact with other people, especially during these most important college years.”

As a result of this article, and the increasing awareness of the lack of diversity on campus, a variety of solutions were sought. For one, the CJC library had added a “Black Culture Corner”, thus providing easier access to resources on the topic. While this was not a large-scale improvement for racial integration and awareness on campus, it was a step forward.

Around this time, a few other larger programs aimed at recruiting more African American students were planned and executed. The CJC admissions staff worked with Franklin and Marshall College and the Upward Bound Program in Pennsylvania with the goal of reaching out to underprivileged African American girls for an opportunity to attend the college.

The admissions staff also worked through the Roxbury Multiservice Center to locate girls from the Boston area who were interested in doing college work. Similarly, the staff worked with the SET-GO program of the Chicago MCA to locate girls from the Chicago area.

Additionally, by December, 1968, the on campus group INTER-ACT was initially able to garner the support of about 8% of CJC students in approaching the Scholarship Committee and the Admissions Committee in an attempt to discuss the possibility of developing a more racially diverse group of students on campus.

Dick Gregory’s Visit to CJC

Before the Event

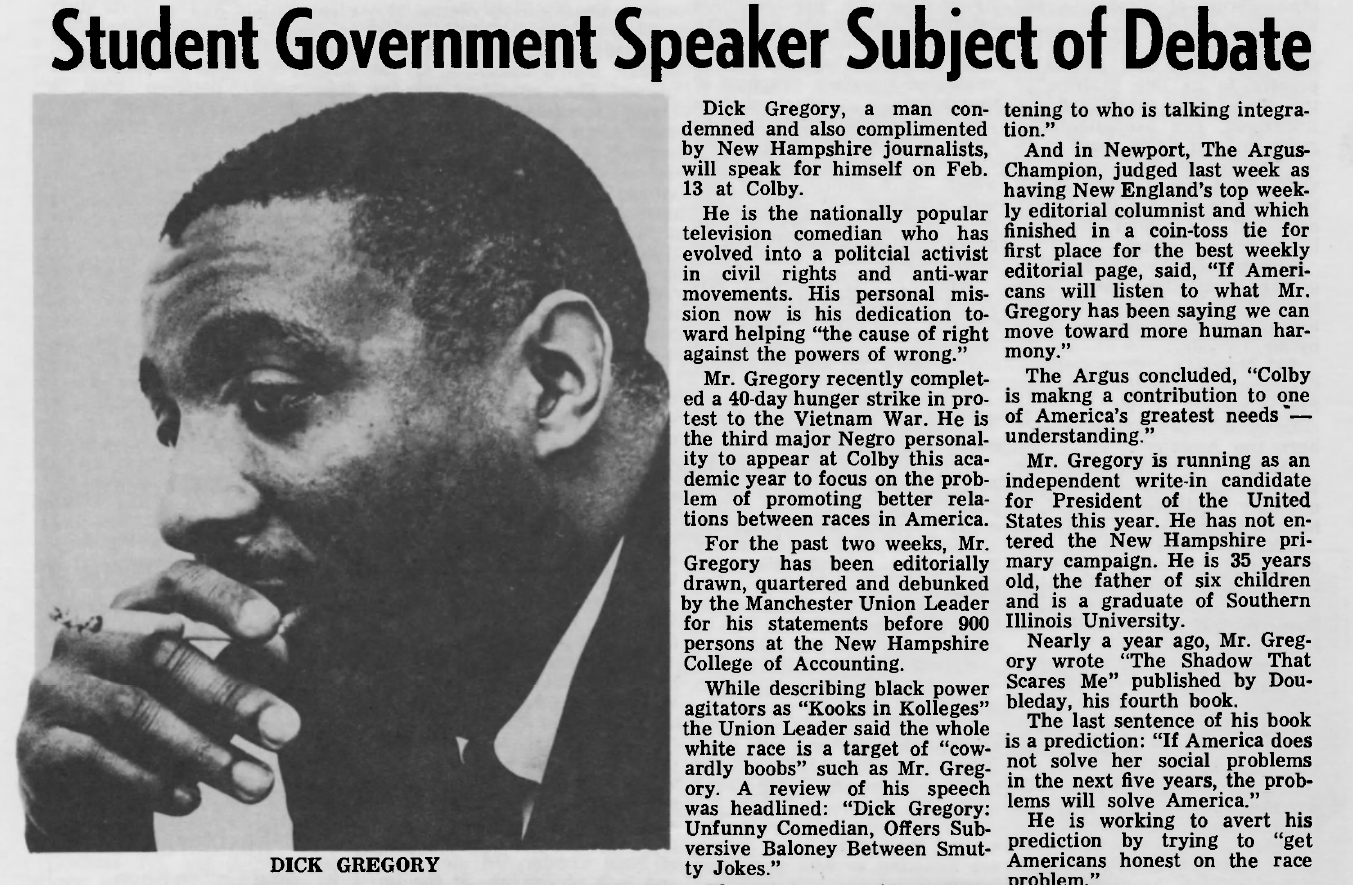

Dick Gregory is a comedian and political activist in civil rights and anti-war movements. Around the time of his visit to CJC, his personal mission was dedicated towards creating harmony between African Americans and Whites in the U.S. He referred to this mission as “the cause of right against the power of wrong”.

Before Gregory, CJC had two other prominent individuals lecture on race and social issues in the U.S. Dr. Kenneth Clark of City College in New York spoke in November of 1967 whose research as a social scientist provided foundation material for the U.S. Supreme Court’s segregation decisions. The second speaker, Dr. James Robinson, was the founder and chairman of Operation Crossroads Africa and visited in December of 1967.

The announcement of his visit to CJC was met with a great deal of controversy. While numerous students found it to be an educational opportunity, there were others that did not want his visit.

For instance, all posters publicizing his visit were removed within 24 hours from the time they were posted. They were, in some area, replaced with scathing articles on his unpatriotic nature. The fact that Gregory referred to the American flag as “a rag” made some CJC students view him as a traitor to patriotism and question whether he was worth paying an admission fee to hear. One student was reported asking, “What kind of American is it who will take this sort of talk, not only sit there by pay to have it thrown in his face?”

On the other hand, in the “To the Editor” section of the February 9th, 1968 Courier, Ellie Mears felt that “if students take the time and pay the money to hear a speaker who has raised so much controversy among the conservatives, radicals, and moderates of this country, the students cannot be said to be ‘stupid’. Interest, inquiry, desire for knowledge, and an attempt for understanding is a step to righting the wrong.”

Similarly, CJC student, Devon McDermott, commented in the “Point of View” section of the February 9th, 1968 Courier saying, “They condemn Gregory as an agitator, a rioter, a troublemaker, and a disturber of the peace. They condemn him for trying to defend his dignity first as a human being, and second as a Negro… That is, they condemn his human effort to defend his humanity.”

Quotes from the Event

The following is a set of quotes from Dick Gregory’s talk at CJC (they are in no specific order):

“I love the way New Hampshire treats its Negroes – all eight of them.”

“I was in London last week and thinking of going to South Africa to get me a white heart.”

“I left the country to protest; LBJ goes half way ‘round the world, gets blessed by the Pope and when he gets back says that nobody else can go out. Well, I told you LBJ there’s a lot of other Baptists who would like to get blessed by the Pope.”

“I told Michelle to go to bed to wait for Santa Claus to come. And she told me that she didn’t believe In Santa Claus because no white man comes in our neighborhood after midnight.”

“I get many ‘hate’ letters, but during my fast I got a separate type which said: ‘Dear Mr. Gregory, This is to inform you that for dinner tonight I had…’”

“Sure, we’d like to make slaves out of all you white folks, but we couldn’t do it. Why it would take one black to master 12 whites. I’d have to get seven jobs to feed all my white slaves. Besides, they could pick all the cotton in two days.”

“I hope to challenge you, the mothers of tomorrow, to decide to make a better world. We’re confronted with so many problems that I feel ashamed to have to place these burdens on you.”

“For over a hundred years we have used the South as a garbage can for racism. Now that they’re starting to put a lid on it, the north is stinking. If these problems existed anywhere else but in America, they would have been solved years ago. But before we can touch the problem we must admit that America is the number one most racist country, black and whites alike. I’m an American and I’m a racist.”

“You young people are dealing with a nation that has gone totally insane. For example, for every day for four months last year, we would read in the newspaper about a clean meat bill. Headlined on one day was; Senate and House Reach Compromise on Clean Meat Bill.’ You know what that means? That means that you don’t eat dirty meat, but you don’t eat clean meat, either.”

“And another mark of insanity is the recent law passed that says I cannot burn an American flag. The shocking thing is that I have a right to freedom of expression – but I can’t burn the American flag which I have bought, which is my property. Perhaps to protect the squirrels and animals we should sneak out to the forest and put flags on them. The American flag is nothing but a rag and the soon we realize this and salute human beings rather than a rag, then, then they might have something to say. The day we all get groovy enough to say you can burn flags, nobody will have to.”

He remarked that “if we learn to live, making a living will be the easiest thing to do.”

“We’re not against whites. We’re against the system that makes you think that we are.”

“When Carmichael makes one of the most honest statements, ‘No more white folks in this movement’ all you whites get upset and say we’re losing support (because we’re being honest). But for every one we lose we gain 12 sincere people. We don’t need any white liberals, they belong with the poor American Indian. We need radicals. When Stokeley says we don’t want no more whites, he was talking ‘bout you whites who come South and march on your red-necked cousins in Mississippi, but wouldn’t take a nigger home to your mammy. When it hits home everybody just runs the other way.”

Returning to the subject of Rap Brown and Carmichael, Gregory quipped, “These two young cats have scared the hell out of this country. Rap Brown doesn’t have a canoe let alone a fleet of ships.”

Aftermath of Event

Dick Gregory’s talk garnered a variety of reactions from the audience. Sue McMichael of The Colby Courier quoted these polarized reactions in her February 15, 1968 article “Man With a Conscience”: they ranged from “I didn’t like him at all” and “He was interesting, but too long” to “He was the most impressive speaker I’ve ever heard.”

On one hand, several students were in agreement with McMichael when she argued that Dick Gregory “is a man with a conscience. While he did not offer solutions to American problems, he certainly demonstrated a clear understanding of what is wrong with America Today. One might be justified in calling Gregory a patriot for he has a definite belief in Democracy and the foundation of our government; that is one of his strongest qualities.”

On the other hand, others responded to Gregory’s visit with negativity. Nina de Schepper from the Colby Courier explains that many students found him to be “manipulative and too idealistic”. Harry Kantor of the CJC Speech Department commented on his speech techniques as “laps[ing] into humor each time after he hit a sensitive spot; through this technique he was able to talk bout sensitive issues more extensively.”

Later Solutions to the Lack of Racial Diversity

In a March 15th article of the Colby Courier, African American student Viv Malloy advocated the use of education as a means to “benefit our brothers and sisters at home in the ghetto.” She goes on to add that, “All of us can do something – no matter how small. But first Americans must realize there is a problem and try to correct it. This can be done by trying to change the ‘racist’ attitudes of other Americans who will, in turn, perhaps influence and affect some of the policies of the United States. We, the youth, should be aware of the problem because we are the fate of tomorrow.”

In April of 1968, a group of about 30 interested girls met in Sawyer Center to discuss the prospects for setting up a “Black and White Summer” program at Colby. Girls volunteered to write to Time and Newsweek to investigate the possibility of getting a financial grant to sponsor the program. Others are writing to such organization as SNCC, CORE, and the NAACP to inquire as to available literature and programs concerning the racial problem.

The program itself involved Colby girls working within their own communities with other whites in an attempt to explain and inform adults about African American problems and why riots begin. Girls were encouraged to go to civic organizations, PTA meetings, churches and any such place where people could gather together and discuss these issues.

As a result of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s death, this program was kick started with the “Hot Time, Summer in the Cities” program on April 15th and 16th, 1968. The program was made possible by Alumni Association of Colby Junior College at the time as well as the Student Government Association. It was intended as an educational movement and as a tribute to followers of King and, most of all, as a plea for racial unity.